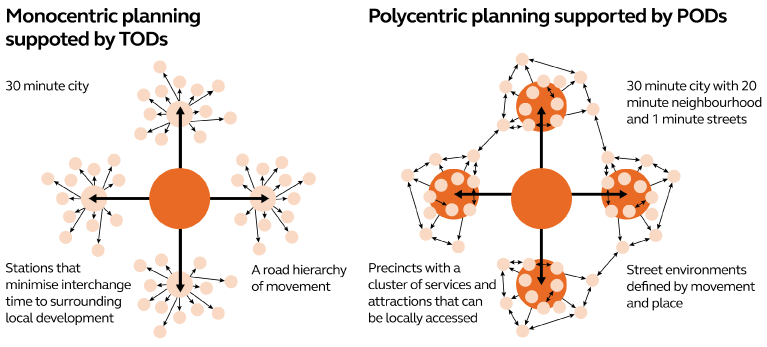

The principle of transit-oriented development (TOD) has been in vogue in urban planning over the last 20 years.

But as we move toward human-centred design and place-based strategies it is timely to ask: does designing and building purely for transit help communities to thrive or should we be shifting to a more people-oriented form of development?

To be sure, trips from A to B may be more efficient with TOD. But for most people, journeys are a mix of travel and activity. When I leave home in the morning I drop the kids at childcare, buy a coffee, pay a bill, and scroll through my news and social media feed before walking into my office in the city. My neighbour loads up her ute just after dawn, buys a bacon roll and extra plumbing supplies on her way to her next job. My other neighbour works from home - his youngest kids get themselves to the local primary school by scooter (often collecting mates on the way), while his eldest catches a bus to high school in the next suburb over.

The local station precinct - designed to TOD principles – might get me into the city more quickly but given the reality of the suburban live described, I’m not sure it really services our neighbourhood.

Breaking the hegemony of the car

Since the arrival of the motor car 100 years ago the development of our cities and suburbs have followed a common trajectory.

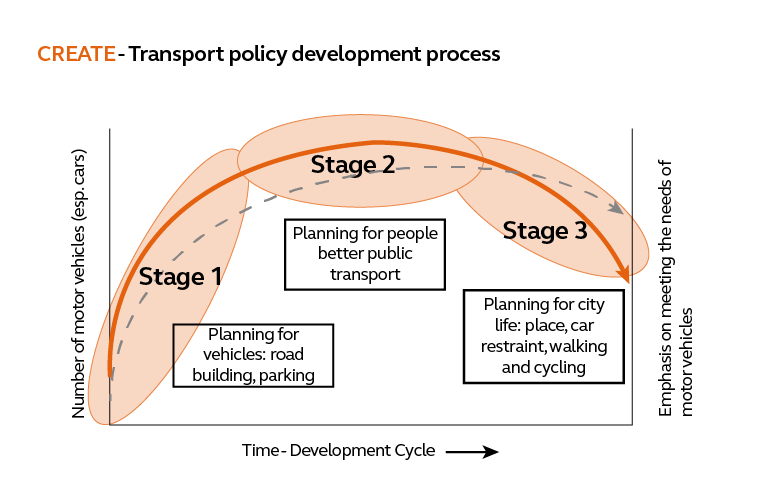

Professor Peter Jones at University College London summarises it in three stages: Planning for cars, then better public transport, and then people and city life, with the policy emphasis on meeting the needs of cars waxing and waning over time.1

In the first stage, as rapid urban economic growth is largely funded by developers and car-owning residents, so new growth areas are usually supported by ‘pro-car’ policies, with priority given to roads and parking areas.

1Professor Peter Jones, “Evolution of urban transport policies: international comparisons”, Centre for Transport Studies, UCL, Presentation to the IATSS GIFTS Workshop November 2015

Unfortunately, in Australia many suburban areas never receive the growth catalyst or economic stimulation to progress past this stage. Instead, they stagnate, and people are forever relying on cars for transport.

On the other hand, when urban areas flourish they soon run up against issues caused by increased car use – namely congestion and pollution. The policy response is typically to fund public transport links and limit car access.

This investment in public transport is harder than the initial urban growth phase, but healthier and more sustainable in the long run. It has the been the end-goal for many TODs to date.

But while TODs facilitate movement of people, the attached public space can be lifeless. Without placemaking in the TOD precinct, mobility hubs are transactional and dull. To my eyes there is nothing more jarring than a transit station in the middle of suburbia - a lone flag of urbanized human connection, drowning in a sea of parking spaces. Any economic uplift and social value associated with our public spaces (including roads and streets) is lost.

As people and urban dwellers, we crave social interaction, activity and community life. This requires a place-based rather than transport-based mindset, one that seeks to contain cars and allocates road space for people walking and cycling, encourages activity and space for public activities - in other words, People Oriented Development (POD).

People-oriented design in practice

If my local station conformed to POD rather than TOD it would be the nucleus of my neighbourhood and not just a transit hub. The surrounding precinct would be a hierarchy of places (just as we classify roads as a hierarchy of movement): the 30-minute city, 15/20-minute neighbourhood and the 1-minute street, each supporting regional, precinct and local activities respectively.

In the 1-minute street local kids play and get themselves safely to school. My neighbour stocks her ute in her 20-minute neighbourhood (where she might run into her elderly neighbour visiting the doctor), and I get myself to the city centre in 30 minutes.

Our transport authority would be planning and measuring our neighbourhood by broader social impacts (including accessibility) rather than peak hour car-journey-time reliability.

Australian cities are presently on a course to ‘city-shaping’ infrastructure – metros, suburban rail, light rail, faster rail, city deals. There are few bigger responsibilities than planning inter-generational infrastructure, because the patterns they lay shape the communities we form.

Infrastructure Australia has recognised the need for place-based infrastructure in its 2021 Australian Infrastructure Plan, released last month. But for such infrastructure to be truly transformational for our communities we need to push the urban design envelope - and put people-orientated development at the heart.

NEXT TIME: Making the POD vision a reality